RESERVATION IN INDIA

Introduction

In early September 2001, world television news viewers saw an unusual sight. A delegation from India had come to the United Nations Conference on Racism in Durban, South Africa, not to join in condemnations of Western countries but to condemn India and its treatment of its Dalits (oppressed), as Indians better known abroad as “untouchables” call themselves. The Chairman of India’s official but independent National Human Rights Commission thought the plight of one-sixth of India’s population was worthy of inclusion in the conference agenda, but the Indian government did not agree. India’s Minister of State for External Affairs stated that raising the issue would equate “casteism with racism, which makes India a racist country, which we are not.”1

Discrimination against groups of citizens on grounds of race, religion, language, or national origin has long been a problem with which societies have grappled. Religion, over time, has been a frequent issue, with continuing tensions in Northern Ireland and in Bosnia being but two recent and still smoldering examples. Race-based discrimination in the United States has a long history beginning with evictions of Native Americans by European colonists eager for land and other natural resources and the importation of African slaves to work the land. While the framers of the U.S. Constitution papered over slavery in 1787, it was already a moral issue troubling national leaders, including some Southern slave owners like Washington and Jefferson. On his last political mission, the aging Benjamin Franklin lobbied the first new Congress to outlaw slavery.

1 “Indian Groups Raise Caste Question,” BBC News, September 6, 2001. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/world/south_asia/newsid_1528000/1528181.stm> Accessed February 27, 2002.

Just weeks before the Constitutional Convention, the last Congress of the Confederation passed the Northwest Ordinance. It was, in part, a successful effort to bar slavery by law from a large part of the new nation.2 Following the Civil War, three amendments were added to the U.S. Constitution to end slavery and protect civil liberties of all citizens under federal law. Congress established and funded a government agency, the Freedmen’s Bureau, to help bring former slaves into the mainstream of American life. Yet with the end of Reconstruction in 1876, the United States relapsed into decades of indifference or worse towards its black citizens. Varying in intensity by region, this included denial of voting rights, intimidation and lynchings, denial of access to adequate public services (including education and water supply), hostile treatment by police and courts, and widespread discrimination in employment and housing.

Not until nearly a century after the Civil War did the United States begin meaningfully to address grievances of black Americans. Black activism and changing white attitudes were central to the process and led to landmark civil rights laws in the 1960s. Since then, a broad system of “affirmative action” has come into being in the public and private sectors. It in effect reserves a portion of available jobs for African Americans (and other minorities viewed as “disadvantaged”). Laws prohibit workplace discrimination, “diversity” has become a watchword, and a social “safety net” assists those in need. However, despite much progress, abundant national wealth, laws, and good intentions, discrimination remains a serious issue for American society.

The roots of India’s untouchability problem recede beyond history as does the caste system that gave rise to it. This is different from the American setting, where the population is not divided into a “natural” hierarchy conforming to religious belief, with the lowest sector regarded as polluted and “untouchable.” Nevertheless, there are some parallels with what happened in the United States. Untouchability inspired many Indians to work for reform, including leaders of the independence movement like Nehru and Gandhi. Efforts to help the Dalits began in the 19th century, first under British colonial administration and, later, from 1947, under India’s independent government. Untouchability, like slavery in America, was prohibited by constitutional provision. As in the United States, laws, administrative regulations, and commissions have anchored official efforts. At the center is a network of government-managed “reservations,” positions set aside by quota in legislative bodies, in government service, and in schools at all levels. The hope is that the “Scheduled Castes,” as Dalits are officially known, can use such opportunities as springboards for better lives for themselves and for integrating themselves more fully into the life of the country. (The situation of India’s “Scheduled Tribes” (ST) is generally similar to that of the Scheduled Castes (SC), but is beyond the scope of this paper.)

2 Article 6 of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 reads: “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory . . .”

This paper traces the complex background of the Dalit issue and analyzes the efforts of the Government of India, starting in the colonial period, to use a reservations policy to benefit the Scheduled Castes. The question to be answered is whether nearly seven decades of implementing reservations have paid off in terms of giving Dalits a bigger stake in Indian society. The thrust of the argument is that the origins of untouchability make reform difficult, that Dalits in many parts of India remain targets of discrimination and abuse, and that extensive government remedial efforts have often been inefficient and even corruption-prone, but that overall Dalits as a group have made significant progress.

CHAPTER I

DEVELOPMENT OF RESERVATIONS POLICY IN THE PRE-INDEPENDENCE PERIOD

The Caste System

Hindu society is divided into four varna, or classes, a convention which had its origins in the Rig Veda, the first and most important set of hymns in Hindu scripture which dates back to 1500-1000 B.C.3 At the top of the hierarchy are the Brahmins, or priests, followed by the Kshatriyas, or warriors. The Vaisyas, the farmers and artisans, constitute the third class. At the bottom are the Shudras, the class responsible for serving the three higher groups. Finally, the Untouchables fall completely outside of this system. It is for this reason that the untouchables have also been termed avarna (“no class”).

Jati, or caste, is a second factor specifying rank in the Hindu social hierarchy. Jatis are roughly determined by occupation. Often region-specific, they are more precise than the sweeping varna system which is common across India and can be divided further into subcastes and sub-subcastes. This is also the case among untouchables. Andre Beteille defines caste as “a small and named group of persons characterized by endogamy, hereditary membership, and a specific style of life which sometimes includes the pursuit by tradition of a particular occupation and is usually associated with a more or less distinct ritual status in a hierarchical system.”4

3 C.J. Fuller, The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 12.

4 Andre Beteille, Caste, Class and Power: Changing Patterns of Stratification in a Tanjore Village (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996), 46.

Jatis in the three highest varnas in the hierarchy—Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaisyas—are considered “twice-born” according to Hindu scripture, meaning they are allowed to participate in Hindu ceremonies and are considered more “pure” than the Sudras and “polluting” untouchables. This concept of pollution versus purity governs the interaction between members of different castes. The touch of an untouchable is considered defiling to an upper-caste Hindu. In southern India, where caste prejudice has been historically most severe, even the sight of an untouchable was considered polluting. Untouchables usually handled “impure” tasks such as work involving human waste and dead animals. As a result, until reforms began in the 19th century, untouchables were barred from entering temples, drawing water from upper-caste wells, and all social interaction with upper-caste Hindus (including dining in the same room). These social rules were strictly imposed and violators were severely punished; some were even killed.

Despite constitutional prohibitions and laws, most recently the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act of 1989, violence and injustices against untouchables continue today, particularly in rural areas of India.5 Accounts of caste-driven abuses continually appear in Western media and surely affect foreigners’ perceptions of India. American economist Thomas Sowell drew on a 1978 case in which an untouchable girl had her ears cut off for drawing water from an upper-caste well in one of his books.6 More recent examples include Dalit students at a government school in Rajasthan who were punished for asking to drink water from a pitcher used by higher caste students and a Dalit in Punjab who was murdered by “affluent Rajput Hindu youths” after his dog ran into a Hindu temple.7

5 Since the early 20th century, several terms have been used to describe the same group of people. The earliest and still most widely known terms are “untouchables” and “outcastes.” Gandhi, because of the unfavorable connotation of “untouchable,” dubbed them “harijans” (children of God). From the 1930s, they have also been known collectively as “scheduled castes,” after the schedules appended to laws affecting their status. In the 1970s, they came to call themselves “Dalits” (the oppressed).

6 Thomas Sowell, Preferential Policies: An International Perspective (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1990), 92.

In its latest published report, the Government of India’s National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes states that “…even after 50 years of Independence Untouchability has not been abolished as provided in Article 17 of the Constitution & incidents continued to be reported.”8 For 1997, the Commission lists 1,157 “registered” cases of abuse of untouchables and tribals. An independent overview is provided annually by the U.S. Department of State in its annual report to Congress on worldwide human rights practices. For India in 2001, the Department commented, inter alia, that

• Dalits are among the poorest of citizens, generally do not own land, and often are illiterate. They face significant discrimination despite the laws that exist to protect them, and often are prohibited from using the same wells and from attending the same temples as higher caste Hindus, and from marrying persons from higher castes. In addition they face segregation in housing, in land ownership, on roads, and on buses. Dalits tend to be malnourished, lack access to health care, work in poor conditions, and face continuing and severe social ostracism.

• The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act lists offenses against disadvantaged persons and provides for stiff penalties for offenders. However, this act has had only a modest effect in curbing abuse. Under the Act, 996 cases were filed in Tamil Nadu and 1,254 cases in Karnataka in 2000. Human rights NGO’s allege that caste violence is on the increase.

• Intercaste violence claims hundreds of lives annually; it was especially pronounced in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh.9

In addition to specifying an economic and social role, caste is also accompanied by certain popularly held generalizations. Brahmins, for instance, are often believed to be fair-skinned, sharp-nosed, and having more “refined” features, consistent with their Aryan roots. Untouchables, on the other hand, are commonly held to be dark-skinned and possessing coarse features. Beteille has pointed out that lighter skin color has a higher social value, making Brahmins highly conscious of their appearance.10 A dark-skinned Brahmin girl, for example, is a source of anxiety for her parents since the task of finding a husband is made harder.11 Matrimonial advertisements, a staple in Indian newspapers, are full of families seeking “wheatish” brides for their sons.

7 BBC News, 25 September 2000 and Manpreet Singh’ “Justice Delayed for Dalits,”Christianity Today, Vol.44, Issue 13, November 13, 2000, 34.

8 National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Fourth Report: 1996-97 and 1997-98, New Delhi, 1998, 232.

Nevertheless, there is increasing social mobility, especially in India’s urban areas. Some untouchables and sudras have tried to move up in the hierarchy by adopting customs of upper castes, a process labeled sanskritization. Others have attempted to escape the system entirely by converting to Buddhism or Christianity. The prominent Dalit politician and lawyer, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956), who saw the demolition of the caste system as necessary for the emancipation of India’s Dalits, converted to Buddhism at the end of his life. Over time, significant numbers, although only a tiny portion of India’s Dalits, have followed his example; in November 2001, thousands of untouchables participated in a mass conversion to Buddhism in Delhi.12

Pre-Independence Initiatives to Eliminate Untouchability

Christian missionaries took the lead in adopting the cause of the Depressed Classes seeking to provide welfare for them. By the 1850s, either inspired or shamed into action by the missionaries’ example, Hindu reformers emerged. Jyotiba Phule was one such activist, and in 1860 he called attention to the plight of victims of caste discrimination in Maharashtra.13

9 Department of State, U.S.A., Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 2001, (Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 2002), <http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2001/sa/8230.htm> Accessed on March 13, 2002.

10 In fact, the term varna literally means “color.”

11 Beteille 48.

12 “Churches Back Buddhist Conversion of Dalits,” The Christian Century, 5 December 2001, 13.

British and other Indian leaders soon followed suit, spurred on in part by reports of discrimination against Indians in South Africa. Thus, in the 1880s, British officials set up scholarships, special schools, and other programs to benefit the Depressed Classes. Forward-thinking maharajas (princes) in “native” states like Baroda, Kolhapur, and Travancore, which were not under direct British administration, established similar initiatives.14 Ambedkar, from the Mahar caste of Maharashtra, was one beneficiary. The Mahars had a long association with the British-organized Indian Army, in which Ambedkar’s father and grandfather had served. One result was that Ambedkar was able to attend government primary and secondary schools.15 The Maharaja of Baroda, recognizing Ambedkar’s gifts for scholarship, sponsored his study abroad, first at Columbia University in New York, where Ambedkar obtained a Ph.D. in Economics, and later at London University, where he earned a DSc. and entrance to the Bar from Grey’s Inn.16

As early as 1858, the government of Bombay Presidency, which included today’s Maharashtra, declared that “all schools maintained at the sole cost of Government shall be open to all classes of its subjects without discrimination.” Although a 1915 press note revealed that this policy was not being enforced—in one case, a Mahar boy was not allowed to enter the schoolroom, but was relegated to the veranda—the Bombay government maintained its position on the issue, and, in 1923, announced a resolution cutting off aid to educational institutions that refused admission to members of the Depressed Classes.17 Other initiatives followed including the 1943 Bombay Harijan Temple Entry Act and the 1947 Bombay Harijan (Removal of Civil Disabilities) Act. In the United Provinces, now Uttar Pradesh, the 1947 United Provinces Removal of Social Disabilities Act was put in force.18

13 V.A. Pai Panandiker, ed., The Politics of Backwardness: Reservation Policy in India (New Delhi: Konark Publishers Pvt Ltd, 1997), 94.

14 Ibid., 95.

15 “Dr. B.R. Ambedkar,” <www.Dalitawaj.com> Accessed March 12, 2002.

16 “Dr. B R Ambedkar,” <http://www.mmu.ac.uk/h-ss/heh/ambedkar/ambbiog.htm>, Manchester Metropolitan University. Accessed December 28, 2001.

In what is now Kerala, the Maharaja of Travancore announced the “Temple Entry Proclamation” in 1936, in what has been called a “pioneer [effort] in the field of reforms relating to the eradication of untouchability before independence.” Stating that “none of our Hindu subjects should, by reason of birth or caste or community, be denied the consolations and solace of the Hindu faith,” the Maharaja declared the removal of all bars on those denied entry to temples controlled by the Travancore government.19 Other measures affecting what would become the present state of Kerala included the 1938 Madras Removal of Civil Disabilities Act and the 1950 Travancore-Cochin Temple Entry (Removal of Disabilities) Act.20

The Government of India Act of 1919

Caught in the turmoil of World War I, Britain focused its attention on Europe, not on India. Nevertheless, the British passed important legislation during this turbulent period that would have a significant impact on the development of Indian governmental institutions: The Government of India Act of 1919.

17 Department of Social Welfare, Government of India. Report of the Committee on Untouchability, Economic and Educationl Development of the Scheduled Castes and Connected Documents (1969), 3.

18 Ibid., 4-5.

19 Ibid., 3.

20 Ibid., 4.

The Act had its immediate origins on August 20, 1917. With Britain in a war for survival in Europe, in need of continued support from India and the Empire, and desiring to avoid confrontation with the Indian independence movement, Secretary of State for India Edwin Montagu, in an announcement in Parliament, defined Britain’s India policy as:

increasing [the] association of Indians in every branch of the

administration and the gradual development of self-governing

institutions with a view to the progressive realization of responsible

government in India as an integral part of the British Empire.21

Montagu and Lord Chelmsford, then Viceroy, embarked on an analysis of the Indian situation, eventually laying out proposals forming the basis for the 1919 Government of India Act. Despite mention of greater Indian participation in politics, the 1919 Act still contained provisions guaranteeing a continued active British presence and dominance:

While we do everything that we can to encourage Indians to settle their

own problems for themselves we must retain power to restrain them from

seeking to do so in a way that threatens the stability of the country.22

The reforms included devolution of more authority to provincial governments and dyarchy, a system in which elected Indian ministers, responsible to the legislatures, were to share power with appointed British governors and ministers. The Act also addressed minority safeguards, including the particularly vexing issue of communal electorates.

Montagu and Chelmsford firmly rejected communal electorates, characterizing the system as a “perpetuat[or] of class division” and a “very serious hindrance to the development of the self-governing principle.” The authors also pointed out another related problem that:

A minority which is given special representation owing to its weak and

backward state, is positively encouraged to settle down into a feeling of

satisfied security; it is under no inducement to educate and qualify itself to

make good the ground it has lost compared with the stronger majority. On

21 Sir Harcourt Butler, India Insistent. (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1931.) 73.

22 Government of Britain: India Office. Report on Indian Constitutional Reforms (Montagu-Chelmsford Proposals), (1918), 7.

the other hand, the latter will be tempted to feel that they have done all they

need do for their weaker fellow countrymen and that they are free to use their

power for their own purposes. The give-and-take which is the essence of

political life is lacking. There is no inducement to the one side to forbear, or

to the other to exert itself. The communal system stereotypes existing relations.23

Despite their repudiation of communal electorates, Montagu and Chelmsford realized it would be unfeasible to take away communal representation already granted to Muslims by the 1909 Morley-Minto reforms. At Lucknow in 1916 the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League had agreed to separate electorates for Muslims. Britain for political reasons was not willing to risk the combined ire of these Indian groups. Other, including Sikhs, Anglo-Indians, Europeans, Indian Christians, and non-Brahmins, also clamored for special representation, but Montagu and Chelmsford largely resisted their demands—they did grant the Sikhs (described as a “gallant and valuable element to the Indian Army”) communal representation—proposing instead a system of nomination. If nomination proved ineffective, they proposed reserving seats for communities in plural constituencies, but with a general electoral roll.24

In Britain, the decision against communal electorates was controversial. Indian moderates and some British members of Parliament (MPs) supported the Montagu-Chelmsford position. (One MP effusively praised the Montagu Report, but lamented that such an excellent product came from a Jew and not a “real” Englishman.) However, most feared an “oligarchy of Brahmins” if communal electorates were not set up for non-Brahmin Hindus.25 Several factors contributed to such “Brahminophobia,” a fear that had been developing even before the Montagu-Chelmsford Report

23 Ibid., 230.

24 Ibid., 111-112.

25 Eugene Irschick, Politics and Social Conflict in South India: the Non-Brahmin Movement and Tamil Separatism, 1916-1929 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969) 96.

Some Britons perceived Brahmins as “untrustworthy,” oppressive towards the lower castes, and subversive regarding British governmental and social reforms. Valentine Chirol, a prominent Times correspondent, published Indian Unrest, in which he asserted that Brahminism was the biggest threat to the British. The Rowlatt Report of 1918, the product of a study on the causes of political violence in India, described Brahmins as “revolutionaries.” Annie Besant, English-born leader of the “Home Rule” movement for Indian independence, accused Brahmins of repressing the lower castes.26

Another important feature of the 1919 Act was the provision for the appointment of a statutory commission after ten years

for the purpose of enquiring into the working of the system of

government, the growth of education and the development of

representative institutions in British India…and …report…to what

extent it is desirable to establish the principle of responsible government,

or to extend, modify or restrict the degree of responsible government

then existing therein.27

The Simon Commission

In keeping with the 1919 Government of India Act, the British government in 1927 appointed a commission to assess the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms and “whether, and to what extent it [was] desirable to establish the principle of responsible government, or to extend, modify, or restrict the degree of responsible government existing therein.” The seven-member commission was headed by John Simon, MP, and included MP Clement Attlee.28

26 Ibid., 146.

27 Butler 78.

28 Nearly 20 years later, Attlee would be Prime Minister when Britain granted India independence.

This “all-white” panel proved controversial. The competence of the nominees was not at issue, but rather the lack of any Indian representatives.29 In protest, Gandhi and the Congress Party, the dominant Indian political party, boycotted the Commission30 and protest demonstrations in India were widespread.31

The Simon Commission toured every Indian province.32 Its findings were based largely on memoranda from the Government of India, from committees appointed by the provincial legislative councils, and from non-official sources.33 The final report contained recommendations for reform.

One area the Commission identified was the need to safeguard minorities and other disadvantaged members of Indian society. Noting that “the spirit of toleration has made little progress in India,” the Simon report detailed the plight of the Depressed Classes in particular, which it saw not only as a problem of caste, but as an issue with distinct political overtones.

Based on its assumption that the “true cause of communal conflict. . .is the struggle for political power and for the opportunities which political power confers,”34 the committee saw the improvement of the Depressed Classes’ situation as hinging on increased political influence.35 Several options emerged, including pursuing a system of nomination, creating separate electorates, and reserving seats in government within a general electorate.36

29 This lack of Indian representation was indicative of the British desire to maintain control of and influence in India, despite rhetoric of “responsible government.” A statement by, Viscount Burnham, one of the panel members, is telling, “[the main purpose of the Commission is] to prevent the dissolution of the British Empire in India.” (R.W. Brock, ed., The Simon Report on India (An Abridgement) (London: J.M. Dent & Sons Limited, 1930) vi.) Further evidence of Britain’s reluctance to “let go” are provisions in major documents which effectively guarantee a continued presence and element of control. The Simon Report, for example, indicates that “the only practical means of protecting the weaker and less numerous elements in the population is by the retention of an impartial power residing in the Governor-General and the Governors in the provinces.”

30 Butler 78.

31 S.R. Bakshi, Simon Commission and Indian Nationalism (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1976) 65.

32 R.W. Brock, ed., The Simon Report on India (An Abridgement) (London: J.M. Dent & Sons Limited, 1930) vi.

33 United States Office of Strategic Services, The Depressed Classes of India (Washington: Office of Strategic Services, 1943) 31. (Originally classified)

34 Brock 15.

In its consultations, the Simon Commission found that most provincial governments supported a nominating system. The Government of Bihar and Orissa, for example, asserted that a nomination was best since the Depressed Classes were too backward to choose their own representatives.37 Despite these arguments, the Commission discarded the idea, arguing that the Depressed Classes needed opportunities for training in self-government.38

Support for separate electorates was strong among the Depressed Classes. Their representatives proposed combining separate electorates and reserved seats. They also demanded a wider franchise, since property and educational requirements significantly restricted their right to vote and to participate in government. The Bengal Depressed Classes Association, for instance, lobbied for separate electorates with seats reserved according to the proportion of Depressed Class members to the total population as well as for adult franchise. The All-India Depressed Classes Association proposed separate electorates for each of what it termed the four major groups in India: the Brahmins, Muslims, Depressed Classes, and Non-Brahmins. The governments of Assam and Bombay supported similar concepts.39

The Simon Commission rejected separate electorates for the Depressed Classes:40

Separate electorates would no doubt be the safest method of securing the

return of an adequate number of persons who enjoy the confidence of the

Depressed Classes, but we are averse from stereotyping the differences

between the Depressed Classes and the remainder of the Hindus by such

a step which we consider would introduce a new and serious bar to their

35 Ibid., 97.

36 Office of Strategic Services (OSS) 34.

37The committee from Bihar and Orissa called for the creation of separate constituencies for the Depressed Classes, rejecting the nomination scheme.

38 OSS 31.

39 Ibid., 33-34.

40 Although the Commission denied separate electorates to the Depressed Classes, it “felt compelled to continue” separate electorates for the Muslims, Sikhs, and the Europeans. (John Simon, India and the Simon Report: A Talk (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1930).

ultimate political amalgamation with others.41

However, they retained the concept of reserving seats:

The Commission recommends that in all the eight provinces there should

be some reservation of seats for the Depressed Classes on a scale which

will secure a substantial increase in the number of Members of Legislative

Councils drawn from the Depressed Classes.42

Seats were to be reserved for the Depressed Classes in general constituencies and these seats would be filled by election, based on a broadened franchise. The Commission also recommended drawing up rules to ensure the competency of candidates for reserved positions. In addition, provincial governors would have the power to nominate or allow non-Depressed Class members to run for election. Competency was of particular concern to the Commission. Members questioned whether enough qualified candidates would be available if seats were reserved according to the proportion of Depressed Classes persons in the population. As a result, the Commission suggested, “the proportion of the number of such reserved seats to the total number of seats in all the Indian general constituencies should be three-quarters of the proportion of the Depressed Classes to the total population of the electoral area of the province.”43 Again, these measures were regarded as strictly temporary, with the goal that an improvement in the Depressed Classes’ condition would eventually make reservations unnecessary.

The Round Table Conferences

In 1931, sixth months after the Simon Commission’s report was published, a Round Table Conference convened in London to review the Commission’s proposals and how they might be incorporated into a new constitution. This time, there were Indian delegates from various interest groups. Ambedkar represented the Depressed Classes, along with Rai Bahadur R. Srinivasan. Gandhi and his Indian National Congress were conspicuously absent, refusing to participate on the grounds that Congress alone represented Indian opinion.44

41 OSS 34.

42 Brock 97.

43 OSS 35.

How to treat minorities was a major topic at the conference. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald chaired a subcommittee to focus on this problem. Ambedkar and Srinivasan appealed for separate electorates and adult suffrage. Separate electorates were designed to be temporary. After ten years, general electorates with reserved seats would replace separate electorates with the consent of the Depressed Classes and enfranchisement of all adults. In the end, the subcommittee could not reach an agreement, a general reflection of the entire conference, which was inconclusive.

A second Roundtable Conference convened eight months later. Ambedkar and Srinivasan again attended. Gandhi also joined, representing the Congress. Having taken up the cause of the Harijans (“children of God,” a term the Congress leader coined), Gandhi adamantly opposed separate electorates, especially for the Depressed Classes.45 Arguing that untouchability was inseparable from Hinduism, he linked creation of separate electorates for the Depressed Classes to alleged British “divide and rule” strategy and asserted that the group should be included in the main body of Hindus. As a result of staunch opposition from Gandhi and the Congress on separate electorates, the second conference was inconclusive and the minority issue remained unresolved.46

44 Marc Galanter, Competing Equalities: Law and the Backward Classes in India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984) 31.

45 Politically active Dalits consider the term “Harijan” patronizing and condescending. Its use was prohibited in all government business in 1990. (Nabhi’s Brochure on Reservation and Concession (New Delhi: Nabhi Publications, 2001) 335.)

Ambedkar originally had misgivings about separate electorates as well, but was compelled to ask for them at the second Roundtable conference when he felt the Depressed Classes were in danger of not gaining any concessions.47 Earlier in the conference, Ambedkar had attempted to compromise with Gandhi on reserved seats in a common electorate, but Gandhi, who had declared himself spokesman for India’s oppressed, rejected Ambedkar’s proposal, and denounced the other delegates, including Ambedkar, as unrepresentative. At the same time, Gandhi attempted to strike a deal with Muslims, promising to support their demands as long as the Muslims voted against separate electorates for the Depressed Classes. It is apparent that political considerations might have also motivated Gandhi to adopt this position.

Given the failure of the conference to settle minority representation, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, who had chaired the committee on minorities, offered to mediate on the condition that the other members of the committee supported his decision. The product of this mediation was the Communal Award of 1932.48

A Turning Point: MacDonald’s Communal Award and the Poona Pact

MacDonald announced the Communal Award on August 16, 1932. Based on the findings of the Indian Franchise Committee, called the Lothian Committee,49 the Communal Award established separate electorates and reserved seats for minorities, including the Depressed Classes which were granted seventy-eight, reserved seats. Unlike previous communal electorates set up for Muslims and other communities, the Award provided for the Depressed Classes to vote in both general and special constituencies, essentially granting a “double vote.” However, in keeping with earlier special concessions to minorities, MacDonald asserted:

46 Anthony Read and David Fisher, The Proudest Day: India’s Long Road to Independence (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1997) 243-244.

47 Kusum Sharma, Ambedkar and Indian Constitution (New Delhi: Ashish Publishing House, 1992) p.224-25.

48 OSS 36.

49 The Lothian Committee, which included both British and Indian representatives, was formed in 1932 to study extension of the franchise, women’s suffrage, representation of the Depressed Classes and other related issues. Regarding representation of the Depressed Classes, the committee decided that “provision should be made in the new constitution for better representation of the Depressed Classes, and that the method of representation by nomination [was] no longer regarded as appropriate.” For the basis of its inquiry, the Lothian committee submitted questionnaires to each of the provinces, asking for input on how best to secure representation for the Depressed Classes and advising that “the application of the group system of representation to the Depressed Classes should be specially considered.” (Indian Franchise Committee, Report of the Indian Franchise Committee, 1932 (Calcutta: Government of India Central Publication Branch, 1932) 4.

His Majesty’s Government do not consider that these special

Depressed Classes constituencies will be required for more

than a limited time. They intend that the constitution shall

provide that they shall come to an end after 20 years if they

have not previously been abolished under the general powers

of electoral revision.50

Gandhi, who was in the Yeravada Prison in the city of Poona at the time because of his civil disobedience campaign, reacted by declaring a hunger strike “unto death.”51 In his opposition to the Award, he compared the creation of separate electorates for the Depressed Classes to the “injection of a poison that is calculated to destroy Hinduism and do no good whatever.” Others were similarly critical of the Award. Ambedkar felt too few seats were reserved for the Depressed Classes. Rajah, another leader of the Depressed Classes, opposed the separation of the community from the Hindu fold.

As a result of widespread disapproval of the Award and Gandhi’s hunger strike, a new agreement, the Poona Pact, was reached on September 24, 1932. The Pact called for a single (non-Muslim) general electorate for each of the provinces of British India and for seats in the Central Legislature. At the same time, specified numbers of seats, totaling 148 for the provincial legislatures and to be taken from seats allotted to the general electorate, were reserved for the Depressed Classes. In the Central Legislature, the Depressed Classes were to get eighteen percent of the seats. Voting members of the Depressed Classes in each reserved seat constituency were to form an “electoral college” to select four candidates from among their number. The Pact also called for “every endeavor” to give the Depressed Classes “fair representation” in the public services “subject to such educational qualifications as may be laid down.”52 Like each of its antecedents, the system of representation of Depressed Classes by reservation outlined in the Pact was intended to be temporary, continuing, “until determined by mutual agreement between the communities concerned in the statement.”53

50 OSS 37.

51 Jagadis Chandra Mandal, Poona Pact and Depressed Classes (Calcutta: Sujan Publications, 1999) v.

Gandhi v. Ambedkar

The Poona Pact set in motion what one student of caste in India has termed “Ambedkar’s qualified victory over Gandhi and the Congress.”54 Although Ambedkar had given in on the common voting roll, he had ensured that specified numbers of Depressed Classes legislators, nominated by members of those Classes, would be included in Indian provincial and national legislative bodies. The number of reserved seats was higher than in the Award. Gandhi and the Congress had little choice. Unless they came to terms with Ambedkar on reserved seats, they risked a break-up of the Hindu electorate with potentially serious political consequences:

To subtract them [the depressed classes] from the population on which the

52 Text of Pact at www.harijansevaksangh.org/poona, accessed March 12, 2002.

53 Sharma Appendix 1.

54 Susan Bayly, Caste, Society and Politics in India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999) 260.

provinces’ Hindu representation was calculated would make a critical

difference to the subcontinent’s electoral arithmetic, particularly in Bengal

and the Punjab where the balance between Hindu and Muslim was so close.55

The Poona Pact is significant in that it initiated a pattern of political compromise between “caste” Hindus and the Depressed Classes in the allocation of legislative representation and government jobs. Although much has changed in India, seventy years after the Pact 81 of the 543 members of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Parliament, are from what were formerly known as the Depressed Classes and 79 of them hold reserved seats.

A by-product of the Pact was the highlighting of the underlying problems between “caste” Hindus and “outcastes.” Gandhi initiated a national campaign to eliminate the evils of untouchability. Six days after the Pact, with help from wealthy industrialists like the Birlas, he started the Harijan Sevak Sangh (Servants of the Untouchables Society) and its weekly journal Harijan. The serious gulf in Hindu society that continues until now along with the reservations system is evident in an exchange between Gandhi and Ambedkar in the February 11, 1933, issue of Harijan. Having asked Ambedkar for a greetings message for the inaugural issue of Harijan, Gandhi received a blunt reply:

. . . I feel I cannot give a message. For I believe it will be a most

unwarranted presumption on my part to suppose that I have sufficient

worth in the eyes of the Hindus which would make them treat any message

from me with respect . . . I am therefore sending you the accompanying

statement for publication in your Harijan.

B.R. Ambedkar

Statement

‘The Out-caste is a bye-product of the Caste system. There will be outcastes

as long as there are castes. Nothing can emancipate the Out-caste except the

destruction of the Caste system. Nothing can help to save Hindus and ensure

their survival in the coming struggle except the purging of the Hindu Faith of

this odious and vicious dogma.’56

55 Ibid., 261

56 “Dr. Ambedkar & Caste,” Harijan, February 11, 1933, 3.

In his rejoinder, Gandhi noted: “Dr. Ambedkar is bitter. He has every reason to feel so.” Gandhi continued, commenting that Ambedkar’s “exterior is as clean as that of the cleanest and proudest Brahmin. Of his interior, the world knows as little as that of any of us.” Affecting humility, Gandhi announced that Harijan “is not my weekly” but belonged to the Servants of Untouchables Society and that Ambedkar should feel “it is as much his as of any other Hindu.” Then Gandhi went to the heart of the matter:

As to the burden of his message, the opinion he holds about the caste system

is shared by many educated Hindus. I have not, however, been able to share

that opinion. I do not believe the caste system, even as distinguished from

Varnashram, to be an ‘odious and vicious dogma.’ It has its limitations and

its defects, but there is nothing sinful about it, as there is about untouchability,

and, if it is a bye-product of the caste system it is only in the same sense that

an ugly growth is of a body, or weeds of a crop.57

Therefore, according to Gandhi, the “joint fight is restricted to the removal of untouchability,” a fight into which he invited Ambedkar “and those who think with him to throw themselves, heart and soul . . .” Ambedkar preferred to carry on the fight through legal and constitutional measures. His legacy is the existing system of reservations. Gandhi, a Hindu traditionalist, sought to inspire Hindus to cleanse the caste system of the evil of untouchability. Judging from his writings, he saw this as an achievable goal.

Gandhi’s Harijan Sevak Sangh continues his work throughout India.58 While the sincerity of the Society’s efforts cannot be doubted, some Dalits see the organization as paternalistic and condescending. At the Society’s start, Gandhi opposed having a harijan on the board of directors. Some sense of caste attitude comes from a report in Harijan of some early activities. For example:

Under the auspices of the Valmik Achhut Mandal, Jullundur, Punjab,

a well attended meeting of caste Hindus and Harijans was held at Basti

Sheikh with Chaudri Daulatram, a Harijan, in the chair. Master Shadiram,

a well educated Harijan, exhorted his brother Harijans to keep clean and

57 Ibid., 3.

58 The Harijan Sevak Sangh’s activities are outlined on its website: www.hindusevaksangh.org.

give up drink and other bad habits.

Bhagat Dhanna Mal, a prominent Congressman of Ferozepur, Punjab, has

taken a vow to remove the evil practices of untouchability, as far as it lies

in his power to do so. He will gladly respond at his own expense to any

call for help from Harijans in any part of India.59

The Government of India Act of 1935

The reservation of seats for the Depressed Classes was incorporated into the Government of India Act of 1935, legislation by the British designed to give Indian provinces greater self-rule and set up a national federal structure that would incorporate the princely states. The Act went into force in 1937.

The Act brought the term “scheduled castes,” now the Indian Government’s official designation, into use, defining the group as including “such castes, races or tribes or parts of or groups within castes, races or tribes, being castes, races, tribes, parts of groups which appear to His Majesty in Council to correspond to the classes of persons formerly known as “the Depressed Classes,” as His Majesty in Council may specify.”60 This vague classification was later clarified in “The Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1936 which contained a list, or “schedule,” of scheduled castes throughout the British provinces.

All-India Depressed Classes Conference at Nagpur, 1942

Efforts by both Indians and British officials encouraged untouchables and the lower castes to form their own organizations to call for more equitable treatment and to demand economic assistance. Ambedkar was at the center of these activities. Seeking a vehicle to bring pressure to bear on the government to secure more resources for the Depressed Classes he had formed the Independent Labor Party in 1936. Changing tactics, he used a July 1942 All India Depressed Classes Conference in Nagpur to establish an All India Depressed Classes Federation.

59 Harijan, February 11, 1933, 3.

60 Chuni Lal Anand, ed., The Government of India Act, 1935 (Lahore: The University Book Agency) 180.

Among the group’s demands were those for a new constitution with provisions in provincial budgets, specifically in the form of money for education, to support the advancement of the scheduled castes; representation by statute in all legislatures and local bodies; separate electorates; representation on public service commissions; the creation of separate villages for scheduled castes, “away from and independent of the Hindu villages,” as well as a government-sponsored “Settlement Commission” to administer the new villages; and the establishment of an All-India Scheduled Castes Federation.61 When in 1942 Congress Party leaders launched a “Quit India” movement, the British, engaged in a war for survival, rounded up Nehru, Gandhi, and other leaders and jailed them for the duration of the struggle with Germany and Japan. Ambedkar, by contrast, supported the war effort and became a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council. He used his new position to advance the interests of the Scheduled Castes. Ambedkar:

Submitted a memorandum demanding reservation for the Scheduled

Castes in services, and scholarships and financial aid for the promotion

of their education. The government accepted the recommendations,

and in 1943 reservation in services in favor of the Scheduled Castes

became effective.62

He had played the situation perfectly. With independence in sight, Congress leaders locked up, and Britain desiring to keep India quiet Ambedkar had successfully expanded the scope of reservations from legislative seats to government jobs and education.

61 Report of the Proceedings of the 3rd Session of the All India Depressed Classes Conference held at Nagpur on July 18 and 19, 1942.

62 Prahlad G. Jogdan, Dalit Movement in Maharashtra, (Kanak Publications: New Delhi: 1991) 57.

Altruism or Political Interest?

Were these pre-independence efforts to uplift the Depressed Classes driven by simple altruism and the desire to correct past injustices? Or were political interests what motivated British and Indians to act? While one cannot deny that leaders such as Gandhi certainly were sincere in seeking to improve the plight of the “Harijans” and weaker elements of Indian society, scholars have argued that politics influenced and continues today to drive the advocacy of reservations and special provisions for Depressed Classes. Suma Chitnis, for example, has argued that the British saw this issue as useful against Indian independence seekers. Missionaries saw the Depressed Classes as especially amenable to their proselytizing efforts. The Congress Party, the dominant Indian party at the time, sought to keep the Depressed Classes in its fold to prevent political fragmentation of the independence movement (and the Hindu population) and to counterbalance the Muslim League, especially in “mixed” provinces like Bengal and the Punjab. Nevertheless, Congress’ interest was relatively late in coming. Chitnis points out that the Congress Party’s interest in the welfare of the Depressed Classes did not emerge until 1917, when Gandhi made it one of the main planks of the party.63

63 Pai Panandiker 96-98.

CHAPTER II

INDEPENDENCE AND THE CONSTITUTION: FRAMING RESERVATIONS POLICY

On May 16, 1946, the British government released the Cabinet Mission Statement, a set of proposals to guide the framing of a new Indian constitution. By this time, the wheels for India’s independence had already been set in motion by Clement Atlee’s Labor Party government in London. Among other recommendations, the Cabinet Mission laid out a detailed plan for the Constituent Assembly’s composition, such that the body be “as broad-based and accurate a representation of the whole population as possible.” Three categories from which to draw delegates were proposed. In addition to divisions for Muslims and Sikhs, the Cabinet Mission suggested a “general” category which would include all others groups—Hindus, Anglo-Indians, Parsis, Indian Christians, the Scheduled Castes and Tribes, and women, among others. Delegates were appointed on the basis of indirect elections in the provincial legislative assemblies.

In March 1947, Britain sent Lord Louis Mountbatten, war hero and royal relative, to New Delhi as the King-Emperor’s last Viceroy. His mission was to transfer power to an independent Indian government. In the end, power was transferred to two successor entities, Pakistan on August 14, 1947, and India on August 15, 1947.

Under the Cabinet Mission plan the Constituent Assembly was to consist of 389 seats, 296 of which were filled by delegates elected from the directly-administered provinces of British India and 93 of which were allotted to the princely states. The total number of seats was based on an undivided India, and, overall, represented a cross-section of the population of the country. Given the Muslim League’s boycott of the Assembly, the impact of partition and subsequent migration, and the lengthy process of integrating the princely states, the number and distribution of seats continually fluctuated from the time of the first meeting on December 9, 1946. With the 1947 partition, many Muslim delegates left for Pakistan, terminating their membership in the Assembly. As a result, the body was reorganized. By November 26, 1949, it consisted of 324 seats, divided among the provinces and the princely states and representative of all major minority groups.

The make-up of the Constituent Assembly reflected the reality of what groups wield power in India, then and now. An analysis of membership in the most important advisory committees of the Constituent Assembly found that 6.5 percent were SCs. Brahmins made up 45.7 percent.64 Minority and Scheduled Caste delegates did have some influence during the Assembly proceedings, with several holding significant positions. Dr. H.C. Mookherjee,65 an Indian Christian, was Vice-President of the Constituent Assembly as well as Chairman of the Sub-Committee on Minorities. However, by far the most important was Dr. Ambedkar.

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), India’s first Prime Minister and dominant political figure until his death, had already selected Ambedkar, an accomplished lawyer, as his Law Minister. A Brahmin himself, Nehru sought to build a secular India free from caste discrimination. He was among the “many educated Hindus” opposed to the caste system as noted by Gandhi in his 1933 Harijan exchange with Ambedkar (above). Given Nehru’s views and Ambedkar’s talents, it is not surprising that Ambedkar became chairman of the drafting committee for India’s new constitution. It was also an astute political move for both leaders. For Nehru, it kept the independently minded Ambedkar “on board” with the government at a critical time; for Ambedkar, it was an opportunity to influence preparation of the new constitution and protect Scheduled Caste interests.

64 Christophe Jaffrelot, India’s Silent Revolution (London: Hurst & Co., in publication), 208, citing research by G. Austin in The Indian Constitution, Appendix III.

From the outset, the Constituent Assembly laid out clearly its objectives and philosophy for the new constitution. Several of the framers’ main goals, articulated in the “Objectives Resolution,” included guarantees of equality, basic freedoms of expression, as well as “adequate safeguards…for minorities, backward and tribal areas, and depressed and other backward classes.” These principles guided the delegates throughout the Constitution-making process.

The Assembly set up a special Advisory Committee to tackle minority rights issues. This committee was further divided into several subcommittees. The Subcommittee on Minorities focused on representation in legislatures (joint versus separate electorates and weightings), reservation of seats for minorities in cabinets, reservation for minorities in the public services, and administrative machinery to ensure the protection of minority rights. After extensive research and debate, the Subcommittee on Minorities drafted a report of its findings for submission to the Advisory Committee. The latter supported most of the Subcommittee’s recommendations.66

Vallabhbhai Patel (1875-1950), Chairman of the Advisory Committee and the most powerful member of the governing Congress party after Nehru, submitted the Report on Minority Rights to Rajendra Prasad, President of the Assembly, and on August 27, 1947, the Assembly convened to discuss the Report. Patel opened the debate by presenting the Advisory Committee’s main recommendations. Rejecting separate electorates—Congress wanted no repeat of the separate electorates granted to the Muslims by the British—and a “weightage” system, the Report endorsed the creation of joint electorates and proportional representation. Reservations were approved for minorities, as long as the reservations were in proportion to the population of the targeted groups. Some minorities, like the Parsis, voluntarily gave up this right.

65 His name indicates his family was Bengali Brahmin by background.

Treatment of the Scheduled Castes was extensively debated. Efforts by Ambedkar and his allies to craft a provision requiring a “tripwire” 35 percent of Scheduled Caste votes in a constituency reserved for the Scheduled Castes failed. The principle of common voting and reserved seats in legislative bodies throughout the country was retained despite strong opposition from influential Constituent Assembly members like Nehru.67 However, the colonial-era system of having the Scheduled Castes choose candidates for reserved seats through local “electoral colleges” was dropped. Throughout the debate, caste Hindus permitted nothing that would suggest splitting off the Scheduled Castes in an electoral sense from the Hindu community.68

Reservations Under the Constitution69

On January 26, 1950, India ended its “Dominion” status, became a republic, and put in effect its new constitution. With an entire section dedicated to “Fundamental Rights,” the Indian Constitution prohibits any discrimination based on religion, race, caste, sex, and place of birth (Article 15[1]). This law extends to all public institutions, such as government-run educational facilities, to access to hotels and restaurants, public employment and public wells, tanks (manmade ponds for water supply and bathing), and roads. The practice of untouchability is declared illegal (Article 17).

66 Kamlesh Kumar Wadwha, Minority Safeguards in India: Constitutional Provisions and Their Implementation (New Delhi: Thomson Press (India) Limited, 1975) 47-68.

67 Nehru maintained this position when backward caste leaders lobbied to extend job reservations to backward groups in the 1950s, remarking “I am grieved to learn how far this business of reservation has gone based on communal or caste considerations. This way lies not only folly, but disaster.” Steven Ian Wilkinson, “India, Consociational Theory, and Ethnic Violence,” Asian Survey. Vol. XL, No.5, September/October 2000, 774-775.

68 Jaffrelot, op. cit., 92-95.

69 The Constitution of India: A Commemorative Edition on 50 Years of Indian Constitution (New Delhi: Taxmann, 2000).

Significantly, Article 15, which prohibits discrimination, also contains a clause allowing the union and state governments to make “any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.” This language was added in 1951 within weeks of a Supreme Court decision outlawing quotas in school admissions. The speed of the amendment is indicative of the strong political support for reservations, Nehru’s personal views notwithstanding.

Similarly, Article 16, calling for “equality of opportunity in matters of public employment,” contains clauses permitting the “reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State” and another allowing “reservation in matters of promotion” for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.70

A separate section of the Constitution, “Special Provisions Relating to Certain Classes,” requires the reservation of seats in the “House of the People,” or Lok Sabha, and the Legislative Assemblies of the states for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.71 The numbers of reserved seats are determined by the proportion Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe members to the general population, based on population estimates from the most recent decennial census. The President of India and the Parliament, in consultation with the state governments, determine the list of groups qualifying as Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and “backward classes.”

70 The Consitution defines the “State” as the “Government and Parliament of India and the Government and the Legislature of each of the States.”

71 The draft constitution, produced by the Constituent Assembly’s Drafting Committee headed by B.R. Ambedkar, included Muslims and Indian Christians among the beneficiaries of reservations in legislatures.

Several safeguards accompany these provisions for reservation. First, the Constitution originally required the reservation of seats in the Lokh Sabha and state legislatures to end after ten years. After five amendments, the policy is now set to expire on January 25, 2010. Secondly, regarding the reservation of jobs, Article 335 of the Constitution mandates that the “claims of the members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes shall be taken into consideration, consistently with the maintenance of efficiency of administration.” Finally, a National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes72 was created to investigate, monitor, advise, and evaluate the progress of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes under the schemes aimed at the socio-economic development of these groups. Another Commission was also created to investigate the conditions of the socially and educationally backward classes.

It is interesting to note that the Constitution’s reservations construct, which explicitly singles out certain castes for special preferential treatment, contradicts the document’s prohibition on discrimination based on caste, race, and other such criteria. Furthermore, India’s caste system itself, with its strict hierarchy dictated by birth, is at odds with the ideals of equality and social justice.

Despite the creation of centrally based commissions to monitor reservations and other schemes, the Constitution gives great liberties to the individual states to determine the quantity and limits of reservation and what, for example, qualifies as the “maintenance of the efficiency of administration.” The clause giving states the authority to formulate and implement policy to facilitate “the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens,” is also decidedly vague. No concrete definition of “backward” is provided either. In addition, though a specific—if, in practice, flexible—time limit is placed on the reservation of seats in the Lok Sabha and state legislative assemblies, there is no such clause regarding the future termination of reservations of jobs and promotions.

Other Legal Protections for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

To give teeth to the protections for the Scheduled Castes and Tribes mandated by the Constitution, India’s Parliament has passed two major laws. The Untouchability (Offenses) Act of 1955 (renamed the Protection of Civil Rights Act in 1976) was intended to provide enforcement of Article 17 of the Constitution, outlawing untouchability. It fell short of expectations. In the words of India’s National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, “All the measures taken were not found to be effective enough in curbing the incidents of atrocities on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.”73 In 1989 a new law, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, came into force. Similar to an American hate crimes statute, it provides heavier penalties than under ordinary law for eighteen specified crimes including forcing the eating of obnoxious substances, bonded labor, and sexual exploitation.

72 In 1990, a five-member commission replaced the Officer for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

73 Report of the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Fourth Report: 1996-1997 and 1997-1998, Volume I, 232.

CHAPTER III

AN ASSESSMENT OF RESERVATIONS

As the reservations policy expands, involving more groups of people and continuing to generate debate, so too does the task of assessing this system. A review of the literature reveals entire books dedicated to the issue, and even these efforts cannot fully sort out the reservations puzzle. In order to achieve breadth without losing depth, I have chosen to examine the effectiveness of reservations by focusing on the experience of the scheduled castes (SCs). Furthermore, I will analyze the policy across time, from inception to present, on a national level.74 Narrowing the problem in this way facilitated a more comprehensive study of the domains into which reservations extends—the legislatures, government service, and education. In addition, because consistent and complete state-specific data were unavailable, this assessment of reservations relies primarily on all-India statistics.75

Though the scheduled tribes (STs) and the other backward classes are undoubtedly important players, covering them thoroughly would be beyond the scope of this study. The other backward classes (OBC), particularly since the release of the Mandal Report, have often been at the center of the controversy surrounding reservations. Nevertheless, Oliver Mendelsohn, for example, has attributed the relative lack of controversy over reservations for SCs and STs (compared to that over reservations for backward classes), who are guaranteed seats in legislatures in addition to preferential treatment in education and public employment, to the reservation system’s “failure.” It is for this reason, Mendelsohn argues, that the policy has not generated the animus of a more successful program.76

74 The annual reports of the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, which have been published from the 1950s, along with other Government of India publications were major resources. However, statistics gleaned from these sources were either incomplete or unavailable across time.

75 Oliver Mendelsohn, “A ‘Harijan Elite’? The Lives of Some Untouchable Politicians,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XXI, No 12, March 22, 1986.

In its 50-plus years of operation has the reservations policy achieved positive results? Have the SCs received the social, political and economic uplifting envisioned by the Constitution’s framers? This section will address these questions.

A Survey of Reservations Policy

Government Services

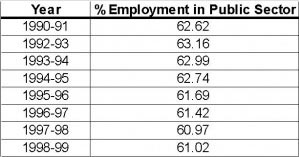

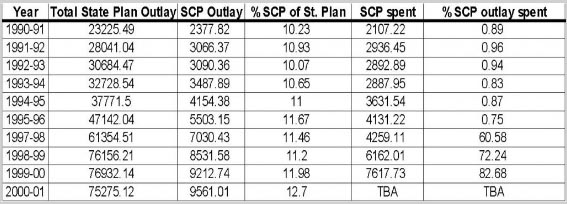

As Marc Galanter has observed, government employment in India is widely considered prestigious and a guarantor of security and advancement.77 Government jobs still account for the majority of jobs in the economy’s organized sector. Table 1 illustrates that despite serious attempts at liberalization beginning in 1991, the public sector continues to dominate the Indian economy and serve as the main source of employment.

Table 1. Estimated Percent Employment in the Public and Quasi-Public Sectors

(in organized sector)

Source: Statistical Abstract, India, 2000, 263.

76 Ibid.

77 Marc Galanter, Competing Equalities: Law and the Backward Classes in India. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1984, 84-85.

As a result, reservations in the coveted area of government services take on increased salience.

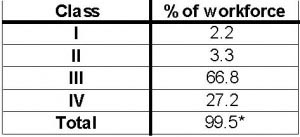

Public sector jobs are divided into four levels, distinguished by income and selectivity: Class I (or Group A), Class II (or Group B), Class III (or Group C) and Class IV (or Group D). Table 2 shows the distribution of jobs among these four categories based on 1994 estimates:

Table 2. Profile of Central Government Employment

Source: Kanchan Chandra, “Why Ethnic Parties Succeed: A Comparative Study of the BSP Across Indian States.” PhD Thesis, February 2000, Harvard University,124.

Notes: Figures do not total 100% because of rounding error

Class I, the highest-paid level, includes members of the elite Indian Administrative Service (IAS), the Indian Foreign Service (IFS), the Indian Police Service (IPS) and connected Central Government services. In the next income bracket, Class II employees comprise officers of the state civil service cadre. Competitive exams and interviews are usually used to fill these top two tiers, which require highly skilled and well-qualified candidates.

In contrast, the bottom two job categories, Class III and Class IV, include low-skill, low-qualification posts such as primary school teachers, revenue inspectors, constables, peons, clerks, drivers, and sweepers. These are typically low-income jobs and are not subject to strict selection processes. Additionally, selecting officials exercise a high degree of discretion in filling posts. Influence plays a major role. This is particularly relevant given that Class III and Class IV jobs make up the bulk of public sector employment in the organized economy. According to estimates from 1994, 94 percent of public sector jobs in the Central Government fell into the Class III and Class IV levels.78 Table 3 summarizes SC representation in the four classes of central government from 1959 to 1995:

Table 3. Percentage of SC Employees in Central Government Services

Sources: National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Seventh Report, April 1984 – March 1985, 5; Commissioner for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Sixteenth Report, 1966-1967, 15; National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Fourth Report, 1996-1997 and 1997-1998, Volume I, 14

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

a.Excludes sweepers

It is clear that there has been a general rise in SC representation in all four categories of employment in central services across time. The SC presence in Class I, for instance, has increased by ten-fold, from 1.18 percent in 1959 to 10.12 percent in 1995. The Class II figures show an upward trend from 2.38 percent in 1959 to 12.67 percent in 1995. The lowest class, which initially had more SC employees in 1959 than any of the other classes had in 1995, has had a slower rate of increase.

While these are all good indications that reservations are working, it is difficult to ignore certain realities that detract from this success. First, SC representation in the Classes I and II, after over 50 years, still fall short of the reservations quota of 15 percent for SCs, while the less-prestigious and lower-paid Class III and IV jobs are amply filled. Even prior to 1970, when quotas were set at 12.5 percent, only Class IV met the quota of places allotted to SCs. However, because reservations apply to only current appointments and the average service career is around 30 years, it is a time-consuming process for the percentage of posts held to equal the percentage of positions reserved.79 The steep increase in Class I and II positions since the 1960s suggests that the percentage of new SC recruits is nearing the SC reservations quota.

78 Kanchan Chandra, “Why Ethnic Parties Succeed: A Comparative Study of the BSP Across Indian States.” PhD Thesis, February 2000, Harvard University, 124.

Secondly, certain posts are “exempt” from reservation. Under the current policy, reservations do not apply to cases of transfer or deputation; cases of promotion in grades or services in which the element of direct recruitment exceeds 75%; temporary appointments of less than 45 days; work-charged posts required for emergencies (such as relief work in cases of natural disaster); certain scientific and technical posts; single post cadre; upgradation of posts due to cadre restructuring (total or partial); and ad hoc appointments arising out of stop gap arrangements.80 As far as scientific and technical posts are concerned, reservations do not apply to positions above the lowest grade in Group I services.

Finally, another factor undercutting the positive trends is the prevalence of false caste certification. Non-SCs, whether out of opportunism or desperation, have been known to pose as SCs in order to take advantage of reserved government jobs, in addition to other benefits afforded to SCs, such as relaxation of maximum age limits and waiving of civil service exams and fees. In an attempt to curb the problem, the Karnataka state government considered issuing caste identity cards to SCs, STs, and OBCs in June 2001. However, the plan was shelved when the authorities realized how costly such a policy would be, given that around 90 percent of the state’s population could be counted as SC, ST or OBC.81

79 Galanter 93.

80 “Nabhi’s Brochure on Reservation and Concessions for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes, Physically Handicapped, Ex-Servicemen, Sportsmen, and Compassionate Appointments.” Delhi: Nabhi Publications, 2001, 43.

Legislatures: The Lok Sabha

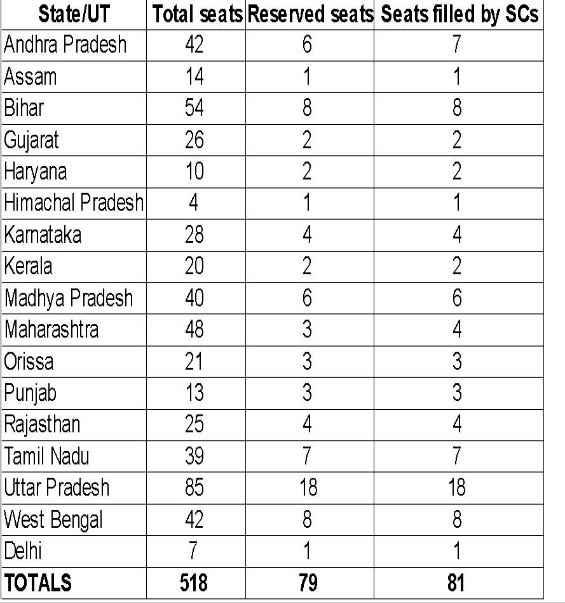

One of the most explicit constitutional provisions concerns the reservation of seats for SCs in the Union and state legislatures. An analysis of the composition of the current Lok Sabha (the 13th, elected in 1999) indicates adherence to the Constitution’s mandate. All seats reserved for SCs are filled, with two states, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, each having an SC Member of Parliament (MP) from a non-reserved constituency (Table 4).

Table 4. Distribution of Seats in Thirteenth Lok Sabha (1999) among States with Constituencies Reserved for SCs

Source: “Seats in the 13th Lok Sabha (1999),” http://education.vsnl.com/journalist/breakup.html. Actual numbers of SC MPs were compiled from MP biographies (http://alfa.nic.in/lok13/biodata). Both sites accessed on March 2, 2002.

81 “SC, ST, OBC families to get caste identity cards,” June 23, 2001. <http://www.ambedkar.org/News/SCST.htm>. Accessed February 22, 2002.

While all seats reserved for SCs are filled, a look at the portfolios and posts held within the 13th Lok Sabha by SCs undercuts the degree of substantive SC representation. Table 5 shows all Lok Sabha committees chaired by and Union Cabinet Minister and Minister of State posts held by SCs:

Table 5. Posts Held by SC Members of Parliament (MP) in the Council of Ministers and Committees of the Thirteenth Lok Sabha

Source: “Parliamentary Committees (Lok Sabha)” http://alfa.nic.in/committee/committee.htm.

Accessed March 2, 2002.

Out of a total of 40 Lok Sabha committees, five are chaired by SCs. Ganti Balayogi, an MP from Andhra Pradesh who served as house Speaker until his death in a helicopter crash on March 3, 2002, headed three of these groups—Rules, General Purposes, and Business Advisory—ex-officio in addition to presiding over the Lok Sabha.82 Elected by the Lok Sabha in 1998, Balayogi was the first SC to be Speaker, a post that in the past has been held by such notables as Vallabhbhai Patel.83 Though the Speaker is mainly responsible for the maintenance of order and the conduct of business in the house, he also can wield considerable influence, especially in cases where a tie vote occurs, and his vote (the only instance in which he can cast one) breaks the deadlock.

82 “Balayogi Dies in Copter Crash,” The Times of India, March 4, 2002. <http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow.asp?art_id=2710212&sType=1> Accessed March 29, 2002.

As a result of the need for governing parties to accommodate party factions with office and to secure representation for certain regions and groups, the Council of Ministers includes 73 ministers. Eight SC MPs currently serve in Union cabinet minister and minister of state positions. Portfolios such as Labor and Employment are not insignificant, but conspicuously absent from the list are such major ministries as Finance, External Affairs, Defense, and Home.

There have been other influential SC MPs in past cabinets. Ram Vilas Paswan, a Dalit from Bihar, has held a seat in Parliament since 1977. In addition to serving as Minister for Labour and Welfare in the V. P. Singh Government of 1989-90, Paswan was also Railway Minister, an office considered a “classic source of patronage,” from 1996-1998.84

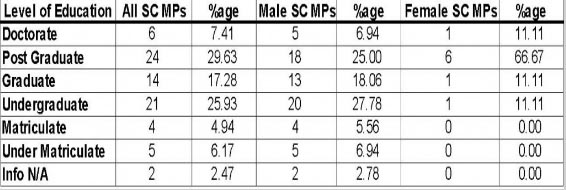

Despite not always controlling “heavyweight” portfolios, SC MPs are generally well-qualified. According to Table 6, 80.25 percent of SC MPs possess at least an undergraduate degree, compared to 87.5 percent for the entire Lok Sabha.85 Breaking down these figures by gender brings out some interesting contrasts. All female SC MPs have had, at the minimum, an undergraduate education and 66.67 percent have had post-graduate training. Among the general pool of female MPs, only 74.5 percent had at least an undergraduate degree. The situation for males is the opposite—only 77.78 percent of male SC MPs had undergraduate degrees and higher while the figure for all male MPs was 88.9 percent.86

83 George Iype, “BJP looks ahead to winning trust vote,” Rediff On The Net, March 24,1998. http://www.rediff.com/news/1998/mar/24BJPwin.htm, Accessed March 2, 2002.

84Untouchable politics and politicians since 1956: Ram Vilas Paswan. <http://www.ambedkar.org/books/tu8.htm> Accessed March 31, 2002.

85 This all-Lok Sabha figure, which includes SCs, is based on the 12th Lok Sabha. Current statistics are not yet available.

Table 6. Educational Attainment of SC MPs in the Thirteenth Lok Sabha

| Source: Compiled from MP biographies. (http://alfa.nic.in/lok13/biodata). Accessed March 2, 2002 |

Given the last available all-India literacy rate for SCs (37.41 percent according to 1991 estimates), the high educational attainment of the majority of SC MPs resonates with what has been dubbed the “creamy layer” effect.87 Critics of reservations have often asserted that the policy has had disproportionate effects, benefiting only the most forward of the SCs—those already in a better position to take advantage of reservations—and facilitating the emergence of an SC “elite.”

In the case of the female SC MPs, their high educational qualifications might also be an indication of an inherent disadvantage in their ability to seek political influence. Perhaps, the fact that 100 percent of the SC women have higher degrees, compared to 74.5% for all women in the Lok Sabha, is indicative of SC females having to overcome both gender and caste hurdles. In order to obtain office, they need to be even more qualified than non-SC females.

86 “Education wise Details of Members of XII Lok Sabha,” http://alfa.nic.in/stat/edu.htm. Accessed March 7, 2002.

87 According to the 2001 census, India has made great strides in literacy in the past decade. Total literacy has increased by over 13 percent since 1991. The SC literacy rate for 2001was not available, but it can be inferred that SCs are part of this upward trend. (Census of India, 2001. http://www.censusindia.net/results/resultsmain.html, Accessed March 30, 2002.)

Data to construct an educational profile for an earlier Lok Sabha were not available for the purpose of drawing comparisons. However, information showing the number of reserved constituencies and the distribution of SC MPs among political parties was obtainable. With the intention of finding as much difference in time as possible and avoiding the shuffling of state borders that occurred in the years after Independence, the third Lok Sabha was chosen for analysis.

In the years between the third Lok Sabha and the present one, the number of seats reserved for SCs has only decreased by one. Comparing the party affiliations of the SC MPs in each Lok Sabha group brings out more striking differences (Table 7):

Table 7. Party-Affiliation of SC MPs in the Third and Thirteenth Lok Sabhas

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Compiled from Lok Sabha party-distribution and SC-constituency data (http://alfa.nic.in/lok13/list/party/13lsparty.htm and http://alfa.nic.in/lok03/list/03lstate.htm). Accessed March 2, 2002

*The party affiliations of two SC members (one from each of the two Lok Sabhas) were not available.